From Jurassic Park to Prometheus, humans meddling with God’s creation is a motif almost as old as writing itself. But recent developments in the field of genome editing, the modification of human, plant, and animal DNA, is promising to transform these tall tales into a reality.

A chain of events, first set in motion by researchers in 2012, culminated in December of last year with the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA)’s decision to approve the first gene editing treatment for humans in the United States. The technology, called CRISPR/Cas9 (Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats/CRISPR-Associated Protein 9) or just CRISPR, has taken the media by storm for its ability to modify sequences of DNA at the level of individual base pairs, the fundamental building blocks of life.

CRISPR has the potential to treat or even cure a gamut of inherited diseases which have long evaded researchers, from cancer to heart disease to AIDS, blindness, and even mental illness. Some think, however, that we shouldn’t be too hasty playing God.

So how did the industry get to this point, what’s making professionals worried, and what could a Jewish lens lend to this polarizing topic?

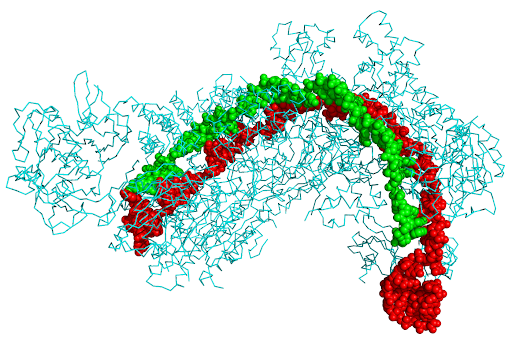

Before we get ahead of ourselves, what exactly is CRISPR/Cas9? In short, CRISPR is a tiny, naturally occurring sequence of DNA found in the immune systems of certain bacteria. It was first coupled with Cas9 proteins for the purpose of editing DNA in 2012, proving to be orders of magnitude faster, cheaper, and more accurate than any previous technique. Since then, it has been used to cure life-threatening diseases, remove allergens from foods, eradicate invasive pests, and produce more efficient biofuels from algae, among many other applications.

During the pandemic, it helped diagnose COVID-19 using its microscopic “genetic scissors” to cleave open and examine patients’ DNA for signs of infection. CRISPR has simultaneously proven promising in the realm of agriculture for engineering larger, more nutritious strains of crops which can better withstand pests and endure harsh winters.

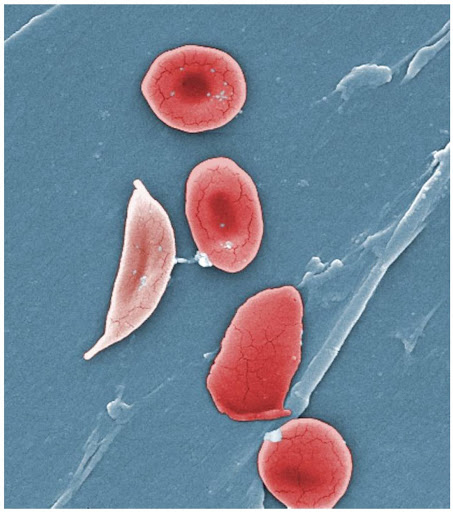

In 2023, the FDA approved CRISPR to be used for the first time in America and for the second time in history to treat Sickle Cell Disease, a debilitating and painful disease in which blood cells come out misshapen and clot. Blood cells are first removed from the patient’s body, modified using CRISPR, then re-injected. Simple enough, right? Unfortunately, CRISPR is incredibly expensive to manufacture and the materials required aren’t readily accessible in many states. Today, this treatment can only be found in a few clinics across the country and comes with an eye-watering price tag of $2.2 million per patient; unsurprisingly, few people have taken up the offer.

Over the past decade, innovations in gene editing have become a hotbed for fierce controversy. The largest dispute by far occurred in 2018 when Chinese researcher He Jiankui announced on YouTube the birth of the first two genetically engineered babies, known under the pseudonyms Lulu and Nana. He’s breakthrough, achieved through the novel use of CRISPR/Cas9, led to an almost universal outcry in the scientific community with scholars worldwide criticizing the immature nature of the technology and denouncing He’s actions as wildly irresponsible. For now, it is illegal to genetically engineer sperm, egg, or embryonic cells in the United States, as these changes would affect every cell in the patients’ body and could potentially be passed down from parent to child. Officials fear that if this technology fell into the wrong hands, say, world militaries, it could be used to fabricate genetic supersoldiers of unparalleled strength and endurance. Similar restrictions exist in China, and He Jiankui was sentenced to three years in prison for his work.

The usage of CRISPR also runs the risk of off-target effects, undesired and potentially dangerous changes to the patient’s genetic code as a byproduct of gene editing. What’s so concerning about these effects is that they are both hard to detect and completely unpredictable, having the potential to cause reproductive issues, birth defects, or even cancer later in life.

To say the future of CRISPR is uncertain would be an extreme understatement. He’s work and other controversies have made it clear that for every new milestone the technology achieves, a dozen new ethical concerns arise. Furthermore, the technology is only in its infancy, making it almost impossible to predict where it will be used next. But while CRISPR/Cas9 might be brand new, the ethical dilemmas it brings to light are rooted in antiquity.

When it comes to grappling with the gray areas of human experience, Judaism is no spring chicken. For thousands of years, the rabbis have tackled some of the most provocative moral dilemmas in society, from class divisions to personal privacy. It might be surprising to hear that Judaism has anything to say whatsoever about CRISPR, a 21st century technology. Nevertheless, the Torah is far from quiet on the subject.

Judaism’s discussion of genome editing begins—yes, really—in the beginning. In Genesis, God instructs Adam and Eve to “be fertile and increase, fill the earth and master it; and rule the fish of the sea, the birds of the sky, and all the living things that creep on earth” (Genesis 1:28). On a cursory reading, God seems to be authorizing humans to dominate the natural world. However, this isn’t the only way to interpret the Hebrew text. Milken Rabbi Candice Levy contends that God made it humanity’s responsibility to nurture and protect the earth, not exploit it for profit. However, as Rabbi Levy points out, the boundary is often unclear: “I think that there’s a fine line between […] using the resources that are available rather than exploiting them.” CRISPR arguably belongs to both categories, seizing the reins of evolution away from mother nature while safeguarding human, plant, and animal life.

Another concept from the Torah that endorses CRISPR is Pikuach Nefesh, our obligation to preserve human life above all else. This rule overrides all other commandments in the Torah, barring murder, idol worship, and adultery, the worst crimes in the Jewish faith. Since in many cases, CRISPR has the potential to extend human life, whether by curing diseases or preventing aging altogether, it falls under Pikuach Nefesh.

This is not to say that genome editing doesn’t get its fair share of religious reproval. One of the many arguments often used against CRISPR and other gene editing technologies is that of humans interfering with God’s sacred plan. In response to this charge, Rabbi Levy presents the scenario of a man and a woman who are considering using CRISPR to prevent their child from inheriting a genetic disease. She asks whether God had a hand in the child’s illness or if it is simply a case of bad luck that the parents are at liberty to correct for. In other words, if God gave us the tools to build an ark, why would we choose to perish in the coming flood?

However, things become more complicated when CRISPR is used for reasons other than directly preserving human life, like enhancing athletic ability, height, memory, or IQ. Rabbi Levy brings up the Jewish concept of Kilayim, which outlaws the creation of new species through intermixing DNA. Whether or not this applies to CRISPR is a subject for debate, but runs the risk of utterly disqualifying the technology under Halakha, Jewish law.

Law codes aside, one final complexity that Rabbi Levy addresses is that of access disparity. She asks whether it is moral to allow a handful of wealthy individuals to rid themselves of disease or extend their lifespans, perhaps indefinitely, while others continue to suffer. However, this level of inequality is nothing new. Existing pharmaceuticals like insulin, which diabetic patients need to live, are so expensive in the U.S. that working-class patients who are uninsured may be forced to ration their insulin to make their supply last until they can afford more. If anything, Rabbi Levy argues, CRISPR will only serve to highlight “the economic disparity that exists in society.”

Rabbi Levy concludes by revealing that the rabbis couldn’t have anticipated the world of today. In their time, Jewish society operated on a 50-year cycle ending with a yovel year, when all land ownership was renounced in a kind of grand reset. This made it impossible for individuals to amass large amounts of generational wealth, removing the possibility for long-term economic disparity. While this law is still observed by many farms in Israel today, universal dependence on farmland as a source of income has since vanished. When asked what the rabbis would think about our modern economic system, Rabbi Levy responds, “I think they would be quite troubled.”

Does this mean that the rabbis’ words have been rendered useless by a rapidly changing society, that their ancient wisdom has no place in the modern world? Actually, it’s the exact opposite. Jewish commentary isn’t some antiquated art form, it’s a mindset. Just as the people of Israel (literally, “struggles with God”) struggle with their creator, we struggle with the scholars who came before us, who shaped Jewish law and ethics into its current state.

At Milken, 11th grade Beit Midrash students participate in this tradition of renewal by discussing modern issues–many of them choose gene editing–through the lens of the rabbis for their final projects. So while there is no true consensus in Judaism on whether gene editing is ethical, the Jewish community, and, indeed, the Milken community, are still debating the issue to this day. As CRISPR/Cas9 technology continues to advance at an ever-accelerating rate, it is crucial that scientists and laypeople alike examine the field with skepticism and a willingness to confront complexities, even those without a clear resolution.

As Jews, we are well-equipped to handle such complexities; it’s in our DNA.