After the Rain: What La Niña Means for California’s Drought

Banks exposed at Bear Gulch Reservoir in Pinnacles National Park

As December drew to a close, rain swept through California, leaving behind a renewed vigor espoused by the new shoots of green blanketing once gray, dead hills and the snow now hiding the dark mountain peaks. Along with the sense of freshness in the air, there was an almost ineffable feeling of hope that California’s perpetual drought would be wiped away. Yet throughout the state, exposed lake and reservoir banks continue to mark where water levels once were, reminding Californians that once the transient effects of the precipitation fade, more struggles with drought are on the horizon.

Despite a relatively wet start, without further rain, 2021 turned out to be the driest year in a century, ending a brief reprieve in the drought. While this year began with desperately needed storms, California might repeat the same pattern as last year and not receive any more substantial rainfall until next winter. This is because it is currently a La Niña, resulting in drier weather as rain is pushed away from the coast. Furthermore, as climate change advances, the highs and lows of precipitation will become more extreme; big storms might appear to reverse the drought, but overall, prolonged dry periods will cause it to persist. As such, early rain becomes all the more significant and California must work to improve sustainability and conservation to make the most of it.

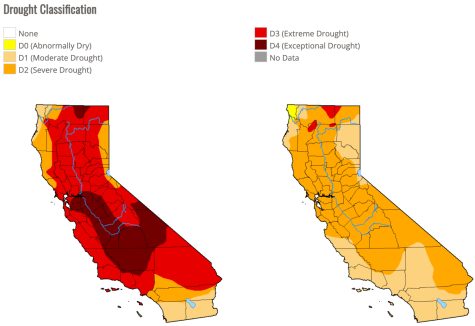

In December, Downtown Los Angeles saw 9.46 inches of precipitation, more than double the typical rainfall at this point in the water year, which extends from October 1 to September 30. According to the U.S. Drought Monitor, produced by the National Drought Mitigation Center, nearly 80 percent of California was suffering from an extreme or exceptional drought, the two highest classifications, before the storm. Afterward, that number was nearly zero.

Importantly, much of the precipitation fell as snow, adding to the Sierra snowpack which supplies 30% of California’s water. During the spring, the snowpack melts and feeds water down streams and rivers to reservoirs, where it can be used during the dry summer months. In a survey at the end of December, the Department of Water Resources (DWR) recorded 78.5 inches of snow at Phillips Station near Lake Tahoe, double the average depth at that time of year.

Despite this positive news, Sean De Guzman, manager of the DWR snow surveys, warned that the drought is not yet over. “A wet start to the year doesn’t mean this year will end up above average once it’s all said and done.” This is already becoming apparent. After the early storms, the snowpack statewide was 160% of the average. Yet now, without much rainfall since then, the snowpack is at its normal levels for February, and will decline below the typical depth if it is not bolstered with more precipitation.

Furthermore, it is a La Niña year in the El Niño Southern Oscillation (ENSO), a recurring climate pattern that affects most of the world. This means that the warmer, drier trend California is experiencing could very well be exacerbated. According to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), during La Niña, strengthened trade winds push the warm water in the equatorial Pacific further west, increasing evaporation and rain in southeast Asia while causing dry air to sink in the central Pacific. This sinking air reduces the west to east flow of the Pacific jet stream, creating a high pressure area that diverts wet weather from central and southern California, resulting in a drier winter.

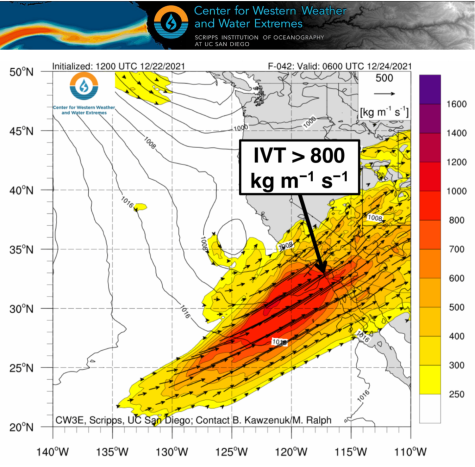

A wet start does not guarantee that the drought will be eased by the end of the year; on the contrary, the nature of California’s rainfall makes the drought unpredictable, even in non-niña years. The majority of rain comes from big storms called atmospheric rivers (AR), sometimes more than 1,000 miles long, ARs like the December storms carry immense amounts of water. In fact, research from the Scripps Institution of Oceanography has shown that one of these extreme storms can contribute 25% of an area’s annual rainfall in a short period of time; 50% of Southern California’s annual precipitation comes in only 40 hours.

Accordingly, without atmospheric rivers, California’s primary source of precipitation, the state plunges into drought. This unpredictability is reflected by 2021, the driest year in a century. From January 26-29 2021, the central coast was hit by an AR that shed 12 inches in Big Sur, destroying a section of Highway 1 and closing the road for several months. The National Weather Service reported that after the rain, the Bay Area had 40% to 60% of normal precipitation for the water year. “While it certainly made a chunk in the deficit, summer remains just around the corner with the hope of more rain before the dry season arrives.” It never came.

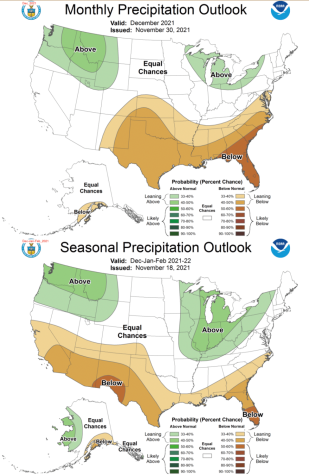

Last year, California suffered an extreme drought, and there’s a possibility this year could be the same. Roughly 33.6 trillion gallons of water fell in 2021, around half of the normal rainfall, while 33.9 trillion gallons have already precipitated this year as of January 1. Even so, because of the expected La Niña conditions like the high pressure area off the coast, the forecast still is not that favorable. In the dry 2020 and 2021, a similar high pressure ridge was found, diverting wet weather away from the state. In the precipitation forecast from NOAA, the December predictions were altered to reflect the atmospheric river, but the overall seasonal rainfall is still leaning to be below average in the stretch of California’s three wettest months. Just like 2021, the state could get one big storm and nothing else for the rest of the year.

Taken together, recent studies have shown that while extreme storms like atmospheric rivers will become stronger and contribute more to California’s precipitation, they will be offset by drier periods in between. Shang-Pie Xie, a climate scientist at the Scripps Institution Of Oceanography, analyzed the results of 16 different climate models and found that climate change enhances the effects of ENSO, increasing sea surface temperatures and the atmospheric pressure response in the Pacific. Warmer oceans cause more water to evaporate, increasing the moisture in the air and accordingly, the frequency of atmospheric rivers, affirming the theory that “warmer gets wetter.”

However, as the state gets hotter and the soil gets drier, more of the precipitation that does come will fall as rain and not as snow, depleting the snowpack and decreasing the amount of water available in the summer months. Additionally, more runoff from the melting snowpack will be absorbed by the ground instead of flowing into reservoirs.

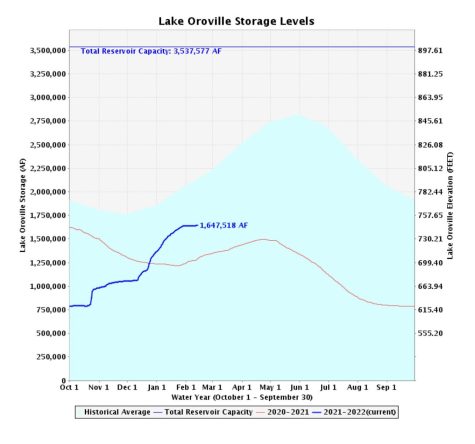

This is already becoming an issue: depleted reservoirs have forced California to choose between providing water now or conserving for the future.

Before the December storms, the Department of Water Resources announced that the state water project would not supply any water to save for a continued drought. With the additional rainfall, that number has gone up to 15%. “But severe drought is not over. Dry conditions have already returned in January. Californians must continue to conserve as the state plans for a third dry year,” DWR director Karla Nemeth explained. Accordingly, California adopted new regulations last month restricting unnecessary water use like overwatering yards, hosing driveways, and watering lawns after rain, in an attempt to reduce urban water use.

Preserving reservoir levels should not happen at the expense of other water sources. During dry years, groundwater accounts for 60% of the state’s water supply, up from 40% in typical years. This places immense strain on these aquifers, underground rock layers that store groundwater. Furthermore, because of the prolonged drought, 63% of wells are currently operating below normal levels, many of which risk soon drying up. After six years of research, the DWR approved dozens of plans by local agencies to improve the sustainability of their groundwater basins and manage their water supply.

This reflects a long term goal to “Make Water Conservation a California Way of Life,” by improving water efficiency through legislation that was passed in 2018 but only now is starting to be implemented. As part of this legislation, the standards for indoor water use will slowly decrease over time with the goal to get closer to efficient water use, or about 35 gallons per capita per day. In concert, higher standards will be enacted for agricultural use, which accounts for 80% of the water used in California, as well as water waste.

Thus, while California is also working to increase its water supply through recycling and desalination projects, ultimately what matters more is how the state and the people deal with the water we have. As climate change progresses and the vagaries of El Niño Southern Oscillation become more extreme, it is essential that we are more aware about the land we live in and our impact on its resources. The drought has become a constant in California, to the point that people become more indifferent to it as it persists and becomes an even bigger issue. One sprinkling of rain can offer false hope that everything is changing for the better, when it’s really only an interlude if we remain passive. As California changes, we have to change along with it.

Ophir Berrin is a staff writer for the Milken Roar. He has always been interested in writing and was drawn to the Roar in 11th grade because he wanted...