Off the Rails? How New Developments in the Los Angeles Metro are a Step Forward – and a Step Back

Riders waiting for the train to pull up at the 7th St. Metro Center

Growing up in Los Angeles, I remember that taking the rail felt like an odyssey (for better or for worse, if you were a boy looking for adventure). With interminable waiting, decrepit terminals and compartments, a labyrinthine process to buy the tickets, and circuitous routes through the city that seemed to go from nowhere to nowhere, the metro came straight out of Greek myth.

However, as anyone who has ridden on the Metro during the Covid-19 pandemic can attest, getting around LA using public transportation is now surprisingly . . . good. With the county’s coronavirus health mandates, the cleanliness of the buses has become more of an emphasis with daily cleanings, and masks and hand sanitizer provided. Now, Google Maps and Metro’s own website provide live information about the location of the buses and trains, making it easier to plan your route and get around.

More importantly, over the pandemic fares have been free to minimize contact and ensure fast boarding times. For the low-income riders who make up 70% of the Metro’s ridership and rely on it daily to get to work, it has had a far more significant impact. By saving the money they would have spent on fares, they are able to cover other bills they need to pay to stay afloat.

Even for Angelenos who can afford to pay, these changes have demonstrated the potential of an improved public transportation network, enabling quick and easy movement across Los Angeles for everyone. Although expected eventually, the Metro confirmed that fare collection will resume January 10, 2022, stopping any hope for the policy’s possible continuation in its tracks. Instead, the city has taken a different approach, investing in the construction of many new rail lines to be the emphasis of Los Angeles’s public transit, leaving the vision of a free bus network behind. So while all of these initiatives signal a greater positive shift for the future of the Metro, the contentious debate over how it should look persists, a conflict between bus and rail that has been present in Los Angeles for generations.

In the early twentieth century, Los Angeles’s rail system flourished under two private companies, Pacific Electric Railway and Los Angeles Railway. Yet, as the Guardian explains, it became clear to these companies that buses were cheaper and could be used more flexibly, they started phasing out rail lines and replaced them with buses. That isn’t the full story, though. In what’s known as the Great American Streetcar Scandal, one company, National City Lines, bought the Los Angeles Railway and was instrumental in the efforts to replace the rail lines with buses. The investors of National City Lines included General Motors, Firestone Tires, and other companies that would benefit from a greater emphasis on gas and roads. While the moribund rail continued to decline for decades, it slowly started to reemerge in the 1980s, leading up to the recent rail boom in Los Angeles.

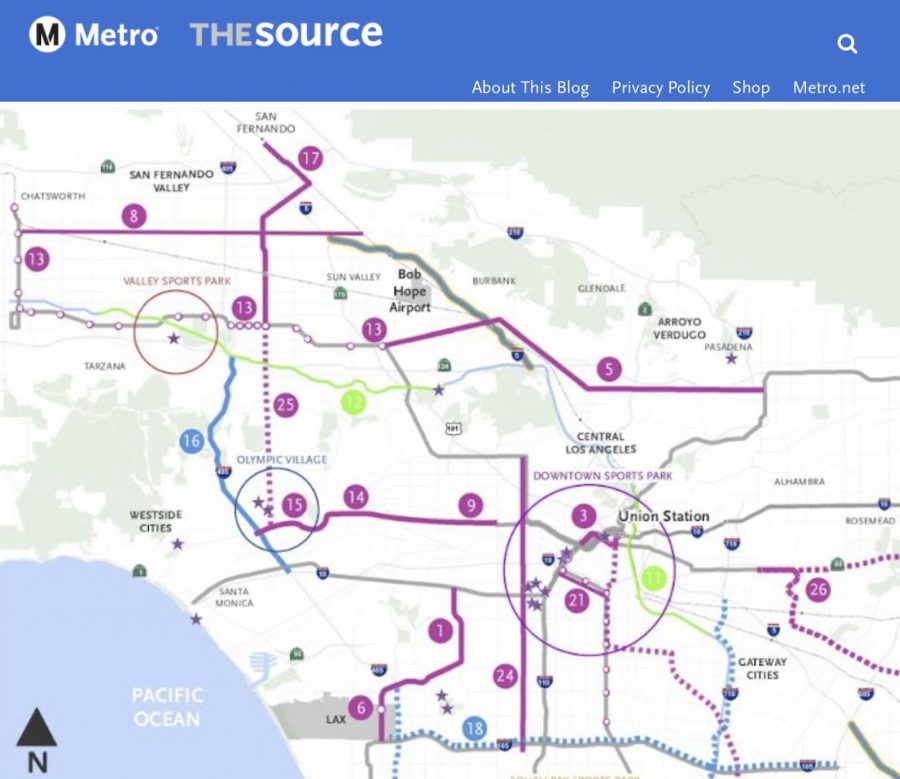

Back in 2018, Los Angeles Mayor Garcetti unveiled the Metro’s 28 by ‘28 plan to pour 42.9 billion dollars into 28 new infrastructure projects to be completed by the 2028 Los Angeles Olympics. The summer games were clearly a motivating factor for this initiative: investing in infrastructure would increase connectivity among the various sporting arenas spread across the county that will be used for the competition, while also decreasing congestion from the thousands of competitors and tourists who will flock to the area. Just as important of a consideration, though, was the impact it would have in the lives of Los Angeles citizens. In Garcetti’s official statement, he noted that “winning the 2028 Olympic games gives us the chance to re-imagine Los Angeles and . . . to transform our transportation future.”

The Reason Foundation, a libertarian think tank, has been very critical of the Metro for framing these projects as beneficial for the Olympics to get funding when they are only marginally related. In defense, James de la Loza, LA Metro’s Chief Planning Officer, says that it’s “not just about the Olympics — yes, that is one big event — but these are 100- or 200-year investments that we’re making.” Some of the major works in progress include the Purple line, which will extend the light rail network down Wilshire, and the Sepulveda Transit Corridor which will improve travel from the San Fernando Valley to Central Los Angeles and LAX. Thus, the Olympics are providing the stimulus to invest in LA’s infrastructure that would not have happened without the necessity for better transportation to win the bid.

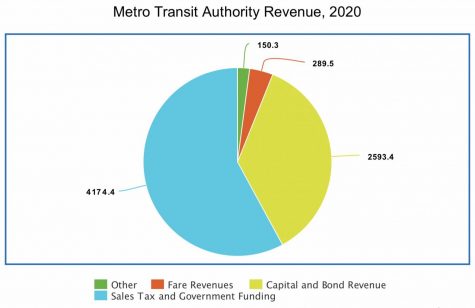

Even though the benefits for the games is just one of the reasons why this public transit renaissance is emerging, the 2028 deadline for the Olympics puts immense pressure on the completion of these projects. The majority of the funding is coming from recent sales tax increases like Measure M, passed in 2016, that raised the sales tax by half a cent. However, 26.2 billion dollars are still needed to advance 8 projects for the 2028 date outside of current revenue sources. In a report published in 2019, the Reason Foundation also concluded that the Metro had bitten off more than they could chew without a clear plan on how to pay for all of the projects, making it extremely risky if they end up without the necessary resources. At first de la Loza was optimistic about finding possible funding, but with Covid-19, “The expected loss of local, state, and federal transportation revenue and additional costs will hamper Metro’s ability to fund the acceleration of the pillar projects,” he wrote to the Metro Board of Directors in 2020.

Furthermore, the Metro’s focus on big construction projects might be misguided, on top of the immense costs that it has accrued. Thomas Rubin, who has 40 years of experience in the transit industry, told the Los Angeles Times earlier this year that “there’s something like 100 [train stations] in L.A. County [as] opposed to 13,000 bus stops.” Most public transit riders rely on the bus network, so when rail is invested in more while letting the buses suffer, overall ridership decreases.

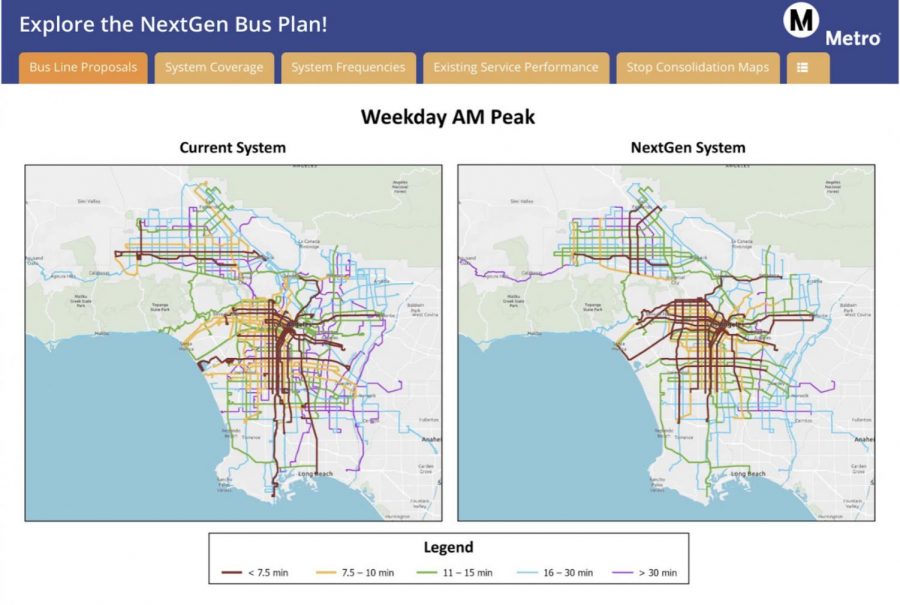

That isn’t to say that buses are not being considered in Los Angeles. As part of the Metro’s vision for 2028, they also introduced the NextGen Bus Plan with the intention of increasing bus speeds and route frequencies, addressing key concerns for many riders as they depend on reliable transportation to get to work on time. In Phase 2 of the plan, which was implemented on September 12, 2021, the Metro consolidated the bus network, removing some buses to improve the travel times of others. In another positive development on September 23, 2021, the Metro announced that as part of the Fareless System Initiative (FSI), bus rides are now free for public school and community college students. They also approved improvements to the LIFE program, which provides discounts to low-income riders.

However, this shouldn’t distract from the fact that the Metro was unable to pass the phase 2 pilot of the FSI, which would make fares completely free for low-income riders, who make up the vast majority of the Meto’s users. According to their presentation, this is because there was “not enough capacity in the current Metro Transit Operations budget” for the 439 millions dollars required over two years.

In other words, because the Metro is pouring all of their resources into completing these large infrastructure projects by the 2028 Olympics, they are unable to pay for other services that many desperately need. The loss of revenue if the FSI went into effect would only account for roughly four percent of the annual budget. However, since the Metro is so desperate to gather additional funding to finish their development projects in time, they are even considering increasing fare costs rather than getting rid of them altogether.

Speaking to people who ride the metro daily, it is apparent the extent of the impact of free fares. Especially during rush hour, when many people crowd the entrances of the buses to get home, returning to any fare collection system would impede the buses dramatically with longer boarding times. TAP cards attempt to ameliorate this issue, replacing the physical exchange of money with contactless payments that work by placing the card on a sensor. Even so, invariably there are other setbacks that can slow the process down, like people thinking they have enough money stored for the fare when they don’t. Unsurprisingly, one rider, who wished to remain anonymous, remarked that having free buses during the pandemic “was great! I was able to save a lot of money!” Others cited free fares as the improvement they would want for the Metro in the future. Some felt that the free fares have made Los Angeles feel smaller and closer because of how easy it was to transfer from one bus to another, making it possible to get anywhere in the city. This is coming from people who didn’t qualify for the LIFE program, demonstrating the impact that this policy has had, even for people that don’t need such support to get by. The priorities of all riders, fast, cheap, and reliable transportation can be simultaneously addressed through improving the affordability of the Metro.

Yet at the same time, having a good rail network in Los Angeles is undeniably important as well. Light rail can carry more passengers and travel at faster speeds than typical buses, which generally have to share the road with other vehicles and deal with stop lights and congestion. Traffic is actually a good point to address as it impacts one of the central priorities of the 28 by ‘28 plan: increasing connectivity and opportunity throughout Los Angeles. Furthermore, although these construction projects require significant funding now, free buses will be a form of social welfare, a constant drain on Los Angeles’s resources.

It is wrong to consider big infrastructure projects or any alternative such as free buses as a panacea if we want to focus on improving public transportation as a means to redefine the city. As long as we maintain such a parochial view on the matter, the discussion will continue to go in circles. The truth of the matter is that both are vital and both should be prioritized, on top of other initiatives like the Next Gen Bus Plan. If the sheer amount of rail construction prevents low-income Angelenos from getting the support they need, it’s a very real issue. There are different kinds of progress – some are extremely apparent and others, although less noticeable, make just as significant of an impact. Although building new rail lines is an important investment for the city for the 2028 Olympics and beyond, it isn’t worth it if people are left behind in the process.

Ophir Berrin is a staff writer for the Milken Roar. He has always been interested in writing and was drawn to the Roar in 11th grade because he wanted...

Eitan • Jan 13, 2022 at 1:18 am

Very well written.