How is Race Taught at Milken?

An Analysis of the School’s Handling of Racial Issues

Image by Brennan Linsley for NPR

“Oh America, you bad b****/ I picked cotton that made you rich/ now my d*** ain’t free”

These Kendrick Lamar lyrics ring through the headphones of many Milken students. The discussion of race has extended beyond classrooms and, quite literally, into the ears of Americans. Race is being taught to us everywhere, and with that, students have been asking for the education they receive to be more representative of the raw and authentic experiences they have been becoming aware of.

As the movement for racial equality comes to the forefront of American politics, a debate over how to teach about race has been invigorated. Students across the country have been demanding a more inclusive and diverse narrative in regards to their curriculum. They are questioning the way in which race has been taught to them, wondering if the history they have been learning is white-washed, and pondering why their English curriculum consists exclusively of white men’s works. While Milken may be limited in its own racial diversity due to the nature of being a Jewish institution, the movement for racial equality has not left the school untouched.

Sitting down with various teachers and department heads at Milken, The Roar sought to understand the ways in which the school handles sensitive topics regarding racial inequality in the classroom. We discussed how Milken has diversified its narrative over the years, and how Milken faculty plan to move forward in an age of heightened awareness of the inequities in our nation.

Mr. Thomas Moran, the instructional leader of the English Department, has been a trailblazer at Milken for diversifying the curriculum when he took over eight years ago. Previously, students were limited to optional seminars about African American literature and women’s literature, which meant that it was entirely possible for students to “scoot through all four years reading only dead white guys,” Moran says. Sensing the need for change, Mr. Moran, Mr. Steele, and the department created the Marginalized Voices core class, which focuses heavily on African American voices, women’s voices, and LGBTQ voices. The curriculum now features works written by people of color such as Yaa Gyasi’s Homegoing and Junot Diaz’s This is How You Lose Her. The 100 seniors who take this class every year also tend to thoroughly enjoy the exploration into contemporary music, including Kendrick Lamar’s To Pimp a Butterfly, and Beyonce’s Lemonade.

Other English courses too, namely AP Language and Composition and American Literature, have been designed to include marginalized perspectives like those of Dr. Martin Luther King, Frederick Douglas, and African American abolitionist writers. In recent years, the 11th grade Civil Rights Tiyul to Alabama has provided for even more opportunities to learn from the lived experiences of African Americans.

Many students may have noticed that the college preparatory classes have historically featured more diverse narratives compared to the higher-level Honors and AP courses, which dive heavily into Greek Mythology, Shakespeare, and classics like George Orwell’s 1984. Moran states that the reason why he feels it may have taken longer to diversify in these areas “is there are a lot of topics that are of great importance and a lot of things that our students should be thinking about today, whether it be the rise of authoritarianism around the world, the erosion of privacy, or the degradation of language.” He adds that sometimes, with regards to novels like Golding’s Lord of the Flies, “you can talk about a subject and get to an understanding of that subject through an abstraction that appeals to the individual and where they are coming from”. For example, although Lord of the Flies does not directly feature the voice of a marginalized person, it is possible to speak about the effects of standing by and enabling power that is gained by oppressing people. He hopes that when students read about the major allegorical events within the book such as the death of Piggy and Simon and see “people that are being shot or brutalized on the news, you still make the connection that this is what we are talking about.”

Additionally, he notes that it has taken him a long time to finally give up teaching famous books like Hamlet as it is difficult for him to imagine sending a student off to a college-level experience without having taught it, especially for those who are on track to study literature or pursue an English major.

That being said, Mr. Moran notes “In the last six to nine months, the urgency and the reality of what’s happening with race and our country has been turned on.” It is due to this that he realized devoting a project to such narratives here and there is not enough. Mr. Moran is considering adding these narratives to his short stories unit and is currently researching African American authors to revamp the play unit for Honors English 9 class.

This tension between the so-called “old white male” curriculum versus a more diversified narrative is one that has been brewing for some time but has reached peak relevance. One key example is the New York Times’ 1619 Project, which seeks to reframe the history of America starting in the year 1619 when the first slave ships arrived from Africa as opposed to focusing on 1776, the year of America’s founding. This initiative has been the subject of recent controversy, with some experts suggesting that it replaces historical understanding with ideology and many others preferring to reframe American history through a more “patriotic” lens, neglecting harsher truths.

History courses have experienced their own share of issues in regards to Eurocentric narratives. In 2014, the College Board decided to modify its Advanced Placement United States History (APUSH) curriculum, opting for a direct tone about racism in America and a generally less Eurocentric perspective. After backlash from some for being “unpatriotic,” the curriculum reverted back somewhat the following year, leaving behind some of the stronger language condemning slavery and oppression. This year, students nationwide created a petition asking for the 2014 curriculum to be brought back, as well as to add more information on policies like redlining, the War on Drugs, and mass incarceration. As of now, this petition has 18,920 signatures.

Ms. Ingrid Guth, Milken’s APUSH teacher, has her own thoughts on the petition. She does not necessarily agree with the petition’s push for what she considers loaded language. Moreover, there are more aspects to the class’s teachings than just the College Board curriculum; the textbook chosen and the teacher’s use of limited class time all contribute to how race is taught within the classroom. Ms. Guth chose the textbook The American Pageant, which she views as having a more conservative framework, in the social sense rather than the political sense, regarding these issues, although it has been revised countless times to reflect more modern values and updated information. In her experience teaching APUSH at a public school in Culver City, one of the most diverse cities in California at the time, she had many students who were able to speak passionately about their personal experiences with racism and discrimination as it relates to the material at hand. To supplement this at a school like Milken, Ms. Guth often uses summer reading to allow students to read detailed, firsthand accounts on topics like southern slavery.

Given that we lack diversity in terms of ethnicity and race, and particularly the African American experience, Ms. Sirida Terk, the middle school Humanities teacher and department chair, has had to work to find an avenue to expose these perspectives to her students. Ms. Terk stresses the importance of firsthand cultural knowledge. She and other staff members created a panel for her students in which they shared their experience growing up as African Americans in different regions and in different eras. This is an integral part of the curriculum because at Milken, as Ms. Terk emphasizes, “We have so much limited exposure to the real-life experience of Black folks, and we genuinely want kids to see real people, who they may interact with and respect, and get a sense of what their life is like, what their challenges have been, and get a sense of what the reality of their life is like.”

Moreover, she thinks that race education should extend beyond the confines of the classroom in order to make a broader, positive cultural shift among Milken students. While it can begin in the classes of the middle school, it should be cultivated each year, culminating with the 11th grade Civil Rights Tiyyul, where connections are made between what students have learned over the years and what is still left to be done. She brought up how Ms. Jackson spoke both at the panel and on Martin Luther King Jr. Day regarding her experience with the N-word being used to discriminate against her as a young child in Nevada. The connection was made between how that word hurt her then and the impact of non-Black students casually utilizing that term today. Ms. Terk thinks: “It’s abstract when it’s somebody else or something I read on the news, it’s concrete when it falls within my circle of obligation.” With that, Ms. Terk notes that there are more people of color or those with people of color in their family within our community than many of us realize, and Milken has to work towards creating a more comfortable and accepting atmosphere for such people.

In her seven years at Milken, she initially saw an eighth-grade theme focused on power and powerlessness and breadth of the African American experience. Then, a shift was made to focus on multiple marginalized groups, such as that of Native Americans, women, and immigrants: the goal being to “provide exposure to as many voices as possible.” In some ways, the nature of classrooms can be a microcosm of America at large. Ms. Terk knows that students are capable of handling serious material early on, and wants to ensure that students are given accurate information, so they are not given a “white-washed or redacted version of current events.” This year, she has seen students make connections between what they study regarding segregation, Jim Crow, and the Civil Rights movement to current events and the protests about racial injustice.

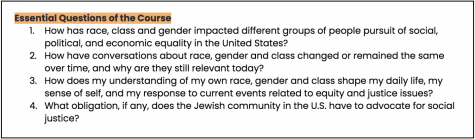

Mr. Kim-Seda has been teaching eighth-grade Humanities at Milken for thirteen years and is taking on a new role as the school’s Instructional Dean and the new teacher for the Race Class & Gender elective at the high school. Like Ms. Terk, Mr. Kim-Seda also notes that the middle school Humanities department has made strides in the inclusion of diverse narratives. The central question of the eighth-grade curriculum is, How do race, class, and gender affect the pursuit of the American Dream. In the past few years, the department has implemented an even deeper exploration of civil rights, the Chicano and Latino civil rights movements, as well as the role of women and Jews during the Progressive Era.

As the new instructor for the Race, Class, and Gender elective (RCG), Mr. Jason Kim-Seda hopes to continue to cultivate conversations about race in the high school. One aspect of the class’s curriculum focuses on the experiences of different marginalized groups and how different governmental policies have shaped their lives.

When asked about how race education varies in a school that lacks racial diversity, Mr. Kim-Seda responded, “Race is a construct. We all have race even though if there’s a white person who thinks about race, since white folks are in the majority, they may think that they’re race-less. And when we talk about race we’re talking about “those” people: brown folks, Black folks, Asian folks, Native American folks, but really I think race education is for everyone.” It is for this reason that the first unit of the RCG class is dedicated to exploring students’ own identities. Learning targets for this section include understanding how students’ personal experiences and family backgrounds have shaped their identity and how they interact with others as well as acknowledging and accepting that the identity of others in their community has been shaped by different yet equally valid experiences and backgrounds.

In terms of objectivity, Mr. Kim Seda notes, “I might insert history instead of objectivity.” His general approach is: “This is history that led to this and here are some objective facts.” He mentions that with realities such as impoverished conditions, redlining, and the roots of policing during times of slavery, “there’s a very real history of Black folks in the U.S being treated as 2nd, 3rd, 4th,10th class citizens.”

It is with this aforementioned spirit of inclusivity and intersectionality that Mr. Kim-Seda hopes to teach lessons that resonate with Milken students and surmount the divisiveness and politicization that is often a byproduct of such conversations. Kim-Seda begs the question: “So can there be this intersection as Jews who have experienced persecution and antisemitism?” He notes that while the experiences of Black people and Jewish people are not the same, he seeks to “find places to have conversations that are less political and more rooted in commonality.”

Even as a non-Jewish teacher, Kim-Seda stresses the importance of Jewish values like the creation of all humans in God’s image and the principle of “areyvut,” being responsible for one another. He hopes to work towards building a “unified approach” to race education: establishing Milken’s beliefs as a school and tackling important conversations instead of shying away from them.

Kayla is a senior at Milken and the Co-Editor-in-Chief for The Roar. Kayla joined The Roar in her sophomore year and since then has enjoyed writing about...

Natalie Tabibian is excited to spend her senior year as Co-Editor-In-Chief! After joining The Roar in her sophomore year, she has written a variety of...